The Worm and the Albatross

/Yesterday, I woke to the sound of rain falling on the roof. My heart lifted and I smiled to myself. There’s been a long, distressing drought over this island in recent years.

But, watching the rain, I also thought of my friend who stayed with her family in Kerala, India, in the aftermath of terrible floods there last August. ’I have never looked at rain with so much horror,’ she wrote.

It twists my mind to imagine it. I’ve written before about the way that longing for rain can become almost a mental illness, at least in those of us from temperate or tropical regions, living in an arid place. In a desert mining town a few summers ago, I saw birds drop dead out of the sky as days were hotter, for longer, than ever. It’s one of several places where I’ve worked and stayed that will probably be uninhabitable twenty or thirty years from now because of climate change.

But yesterday I was distracted from such sombre thoughts by surprise. A long worm contracted and extended its weird moist body along the hotel terrace. I saw it through the glass door as I ate my breakfast.

I lived in the desert long enough that I needed to look closely at the worm for a few minutes to be sure it wasn’t a snake.

I saw another worm while walking to work and stopped to admire its long pink body of muscle. The grey band closer to the front end was where its reproductive organs lay.

I’ve studied invertebrate zoology. Worms are hermaphrodites—they change gender in response to their environment. Some of them reproduce by parthenogenesis, a process of self-reproduction that captured the imagination of lesbian separatists in the seventies.

On my walk, I also saw something squashed, showing brilliant orange and white guts on the road—perhaps it had been a giant land slug. I don’t always get close to roadkill—dead kangaroos smell awful—but this mess reminded me that I spent hours in the lab once, dissecting these prosaic and amazing creatures.

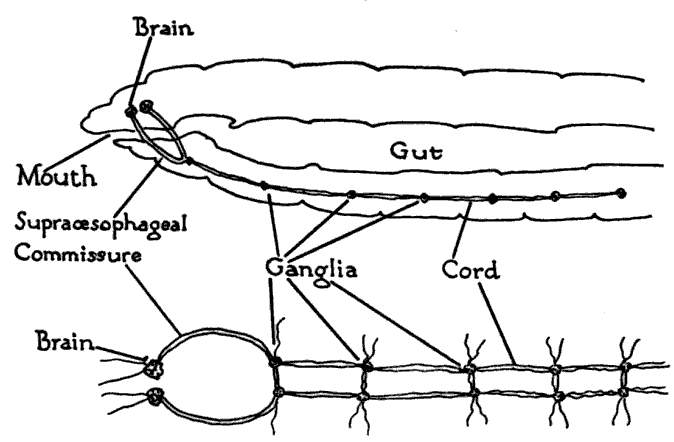

Slugs and earthworms have a notochord, an evolutionary prototype of a spinal cord. We’re related a long way back.

Earthworm’s nervous system, from The mental and physical life of school children by Peter Sandiford, 1913 via Wikimedia.

The smells—of rain on eucalyptus leaves and of fresh water running in the replenished creek behind our clinic—reminded me of a field trip I took to a lake, deep in the bush not so far from here.

In Spring of 1996, after a long journey from the city, our university biology group camped in huts near lake’s edge. On an overcast Saturday, we hunted for weevils, beetles and bugs in the grasses and under the bark of the trees. We took them to a tent set up with microscopes to look at and learn about them. It was a great way to learn about scientific classification and evolution.

At night we had a fire and sang blues songs—Billy Holiday and Gershwin.

On our second night there, a tremendous storm blew in. It was a cold, moonless night. Branches banged against the walls of the hut, thunder shook them. I wondered if the roof might blow off. Inebriated colleagues snored in the bunks, oblivious.

Unable to sleep, I went outside, barefoot in the squelching, rain-saturated grass. Lightning lit the sky mauve, illuminating the tall white gums in its strange, flat light.

The wind whipped up waves on the lightless lake. Smelling and hearing the water, rather then seeing it, I stopped at lake’s edge.

As my eyes adjusted, I saw that the waves had spiralling clouds of coloured light in them. The lights were green, pink, purple and blue.

There was nothing in the wild, dark world to reflect such colours in the water. After a few moments, I realised with wonder that it was life in the surface of the water—bioluminescent plankton glowed where they were stirred up.

Entrance to the lake where I saw the luminous plankton at night. Photographer not credited..

I remembered that night yesterday as I walked to work.

Later on that day, working with a patient, I was on the phone to Canberra. Doctors have to call the national capital to get permission to prescribe certain drugs—medicines which are unusually expensive, prone to abuse or pleasure, or just historically ended up on the ‘Authority’ list.

When the telephonist asked me how I was enjoying the weather I told her that I’d seen a couple of worms that morning. ‘I was so glad to see they still exist. It’s been a long time since I’ve seen one,’ I said.

‘Yes, we need the worms’ she replied. I could feel her smiling under her headset. ‘What is your patient’s Medicare number, please?’

It kept raining, maybe enough to ease the drought.

This town was fortunate. Driving inland yesterday, Claudia and I saw that parched brown fields had greened up.

Perhaps people greeted the earthworms, patted the cows, felt relief deep in their bones, relaxed their muscles as they slept to the sound of pattering rain.

But to the west, south and north of here the storm cells generated wind and hailstones that destroyed houses and boats, ripped ancient trees up and hurled them, pulled down bridges and made roads impassable.

Across the sea on the US east coast, parts of Florida were destroyed. There was a tornado on this island in Queensland this past week. Meanwhile, across the Pacific, a terrifying hurricane has affected everyone in its path and taken many lives. Another typhoon, the worst in twenty-five years, afflicted Japan last month.

The first four major stories on the news last night were about the weather. That seems like a change.

I had the privilege of a medical student’s company over past weeks at work. She was emotionally intelligent, clinically adept and modest. She joined our clinic to learn about Aboriginal cultures, which is an essential aspect of her medical education, part of the curriculum which did not exist a decade or two ago. Having her sit in with me was a constant reminder that progress can be achieved, often by colleagues of mine, standing on the ground built by our elders.

The student was exposed to the complicated medical situations of our patients, and sometimes heard about some of the traumatic social and emotional experiences could have helped create and sustain their maladies.

A few of our patients felt earnestly, and almost unstoppably, compelled to tell their story, especially with a student there. She was glued to her chair, unable to excuse herself from their woeful tales of abuse, exclusion and survival.

‘He’s a man with an albatross around his neck,’ I said of one patient.

’Do you know what I mean by an albatross around the neck? I asked. ‘Do you know the poem, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, by Coleridge?’

She shook her head and I explained. ‘Coleridge took a lot of opium. He had visions, which inspired his poems. The Rime of the Ancient Mariner is one of his best. My grandfathers, both of them self-educated literary men, recited verses of it to me as a child.

‘Let me tell you the story. The poem begins with a wedding guest. He gets stopped before he can get into the wedding by an old man with a glittering eye and a story he has to tell. The wedding guest wants to go inside, but can’t tear himself away from the old man, whose narrative is long and terrible.

My student suppressed a sigh, and I thought that she might know how the wedding guest felt.

‘As a young man, the mariner went out to sea. All went well, until he committed a crime against nature, or at least against the sailors’ superstitions.

He shot the bird that brought the sailors good fortune—an albatross. The huge, dead bird was hung around his neck and somehow he was unable tear it off. It’s grotesque.’

‘Tragedy afflicted the boat.

‘The mariner ends up alone in the ship on a becalmed sea. He’s dying of thirst and surrounded by the rotting corpses of his former comrades. The dead bird is still attached to him.

His comrades cursed the mariner as they died. Illustration by Gustave Dore.

‘In the still water he sees sea snakes and other creatures. He calls it a rotting sea. He says,

Alone, alone, all, all alone,

Alone on a wide wide sea!

And never a saint took pity on

My soul in agony.

The many men, so beautiful!

And they all dead did lie:

And a thousand thousand slimy things

Lived on; and so did I. (IV.54-55)

‘A classic expression of survivor’s guilt.’

‘Yes,’ said the student, lifting her eyebrows. ‘But he was actually guilty,’ she cautiously, probably not sure if she should encourage me.

‘One night,’ I continued, ‘when all is beyond lost, and he’s alone and unable to sleep or to die, the mariner sees luminescent plankton and sea snakes in the black sea by the boat.

‘They light up the sea with blue, green and golden lights. The mariner is astonished by their beauty. He forgets his dire situation momentarily, enthralled by the loveliness of them.

Bioluminescent dinoflagellates (plankton) lighting up a wave at night. Photo by catalano82.

‘From the moment the mariner expresses gratitude and appreciation of Nature, the dead sailors rise up again and the zombie crew sails the unhappy ship home.

He is then compelled to tell his tale to any he can meet and hold with his ‘glittering eye’.’

Some of my patients are a bit like the Ancient Mariner.

As a doctor, I sometimes see the story of people’s interactions with the world expressed in their bodies. Our bodies, so often deemed unfashionable, unacceptable and consequently unloved, are a good place to start accepting the world as it is. Blessing your body might bring you home to your spirit.

Wonder and appreciation of living things is the beginning of healing ourselves and our planet.

It’s a long time since I looked at those irritating, disease-ridden signs of an unbalanced world—a fly or mosquito—with the open-minded curiosity I had as a child. But, as a university student twenty years ago, I found beauty in the colourful gizzards of a cockroach, and was awed by the strange reproductive practices of spiders—handing each other packages of gametes to tuck inside their bodies. And everyone should know that there is medicine in the forest fungi.

It will take much more than insightful observation to change the course humankind is taking on our troubled planet. But thoughts guide our actions, so we might begin material change with a gentle change of mind.

I hope I never have to be frightened of the rain, but there are no guarantees in this world now. So far, you can think of me with a smile when you next see a slimy pink worm, making its way in the rain.

Black-browed albatross, east of Tasmania thumbnail photo courtesy JJ Harrison.